According to the late film critic Roger Ebert, cinema is one of the most effective venues for bringing people from different backgrounds together. “For me, the movies are like a machine that generates empathy,” he once said:

If it’s a great movie, it lets you understand a little bit more about what it’s like to be a different gender, a different race, a different age, a different economic class, a different nationality, a different profession, different hopes, aspirations, dreams and fears. It helps us to identify with the people who are sharing this journey with us.

Ebert described himself as a humanist, and his idea of film as an “empathy machine” fits perfectly with some of the best works of science fiction. Perhaps more than any other genre, science fiction is connected with humanism, which we can define as an ethical stance that emphasizes the rights, responsibilities, and ultimate value of people within a naturalistic framework—that is, a framework that does not rely on supernatural beliefs. Thus, a humanist film, if one could call it that, would depict people helping each other, or forging their own destiny, mainly through reason and compassion. Humanist stories also emphasize the preciousness of sentient life, on the assumption that it is the only one we have—though some films, as we’ll see, have depicted a satirical or otherwise secularized version of the afterlife.

I’ve compiled a list of some of the most profound empathy machines that science fiction has to offer. But before we get to them, a few questions arise. Does humanism have a monopoly on the values described above? Does science fiction necessarily entail humanism? And would a so-called humanist film automatically exclude other traditions and interpretations? The answer to all three is no. So, please consider this the start of a conversation, rather than the definitive conclusion of one.

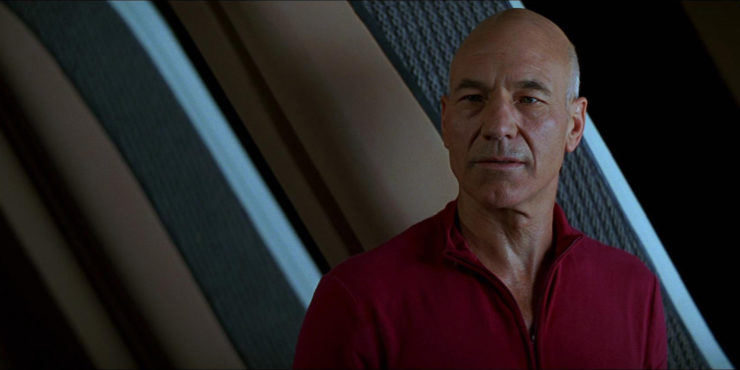

Star Trek: First Contact—Hope for the future of humanity

Star Trek has one of the most obvious connections to humanism in all of science fiction. Gene Roddenberry, the show’s creator, envisioned a future in which humans have overcome the tribalism that has defined the species for so long. Out of that troubled past, they create a world in which the gathering of knowledge and the betterment of people are the driving forces in society.

So why single out this movie, out of all the other Trek films and TV shows? Well, First Contact shows where humanity may be headed before we have a chance to build that ideal society. To save Earth, the crew of the Enterprise must travel back in time to late-21st century America, in the years following a devastating third World War. Despite the major setback to civilization, a group of scientists nevertheless develops and tests a warp drive, which will become humanity’s biggest leap forward in space travel. This leads to their “first contact” with alien life, and a radically new perspective on humanity’s place in the universe.

Trying to stop this event are the Borg, the ubervillains of the Star Trek universe. In many ways, the Borg represent a parody of humanist ethics: they emphasize order, authority, and a cruel logic, at the expense of compassion and empathy. Like so many aliens in Star Trek, they find the humans infuriating—but also unique, beguiling, and sometimes pleasantly unpredictable.

For all the bits of wisdom in the Star Trek canon, Captain Picard’s (Patrick Stewart) exchange with Lily (Alfre Woodard) at the end of the film ranks among the best. Lily, a woman of the 21st century, laments the fact that she cannot join Picard on board the Enterprise. “I envy you,” she says. “The world you’re going to.” “I envy you,” Picard replies. “Taking these first steps into a new frontier.” Whether you are exploring the galaxy in a starship, or whether you’re rebuilding society with shovels and pickaxes, there is always an opportunity to learn, grow, love, and imagine.

Groundhog Day—Creating meaning in a meaningless world

Humanism does not necessarily equal optimism, however. It also acknowledges that even a relatively comfortable life is stuffed with pointless drudgery and disappointing people. Groundhog Day turns this conundrum into an outright horror story, in which the same miserable, frozen day in Pennsylvania repeats again and again for self-centered Phil Connors (Bill Murray). When confronted with this time loop, Phil reacts as many people would—first with denial, then with a nihilistic hedonism, and then with suicidal despair. But through a long process of trial and error, he discovers a foolproof way to find meaning: by becoming a better person, by loving those around him, and by working to make the world a better place, even if he has to start all over the next day. Like the tragic character Sisyphus, Phil finds purpose in the struggle—Albert Camus would be proud!

The director, Harold Ramis, has cited his “Buddish” background as a major influence on the “humanistic” nature of his work. As a result, the thought experiment of Groundhog Day hits close to home for so many viewers, and has enjoyed appeal across religious and secular traditions. Buddhists have interpreted the story as rumination on karma. Roman Catholics have compared Phil’s ordeal to purgatory. And humanists have pointed out how Phil’s journey mimics that of our entire species.

Philosophers of religion are correct when they point out that without a sense of purpose, someone like Phil would look to satisfy their baser instincts, until they eventually grew bored with everything. Though film acknowledges this, the story does not end there. Phil does not merely find meaning—he creates it, which is what we should hope free human beings would do under such circumstances. Eventually.

Defending Your Life—Redemption through action and bravery

If living the same day over and over requires a superhuman resilience, imagine reliving the same life. Upon his untimely demise, Daniel Miller (Albert Brooks) finds himself in Judgment City, where a tribunal will determine if he’s worthy to move on to the next plane of existence. The only problem: Daniel is now approaching his twentieth lifespan on Earth, and his selfishness, cowardice, and shortsightedness have been holding him back for centuries. While slogging through the humiliating trial, in which he has to relive all of his worst decisions, he falls in love with Julia (Meryl Streep), a woman who has clearly “graduated” from life on Earth and is ready for a new adventure. But poor Daniel soon realizes that he is doomed to live another wasted life, while Julia will move on without him.

The movie thus poses a philosophical question: what do you do when you are stuck in place, with no hope of salvation? Daniel answers by finally facing his own fears, and committing to an act of bravery that gives him a chance to be with Julia again. It is only through his own agency, and his connection to other people, that he can improve and move forward. Like a good humanist, he accepts that no one is coming to the rescue, and acts accordingly.

The Martian—Science the shit out of it

If you catch me on a bad day, I’ll tell you that the most memorable quote from Andy Weir’s novel The Martian perfectly sums up the human condition:

“I’m pretty much fucked.”

But there’s hope, for the second most memorable quote sums up the determination of the main character, astronaut Mark Watney:

“I’m going to have to science the shit out of this.”

The Martian thus shows what happens when the human spirit and the rational mind join forces. Lucky for us, the task of adapting this vision for the screen went to director Ridley Scott, who knows a thing or two about depicting a bleak, brutal struggle to survive.

Stranded on the red planet for four years, Watney (Matt Damon) will need all of his abilities and training, along with an unrelenting sense of humor, to make it home again. Meanwhile, his crewmates, led by Captain Lewis (Jessica Chastain), make a moral calculation that is rooted more in empathy than in logic. Their decision to return for Watney is a genuinely moving sequence in what is otherwise an episodic narrative, with the characters solving one puzzle after another, and creating more puzzles along the way—just like real life. In this story, the characters are defined by their will to live, and their willingness to save another life.

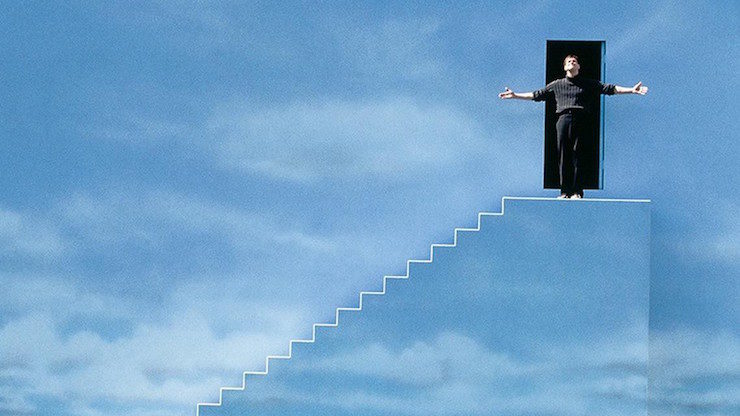

The Truman Show—Discovering the real world

In stark contrast to the drudgery of Mars, Judgment City, and a Pennsylvania winter, we turn to the lovely town of Seahaven, home to Truman Burbank (Jim Carrey) and his perfect wife Meryl (Laura Linney). This Norman Rockwell-esque hamlet is so safe and welcoming that Truman has no reason to leave, right? But no—our hero wants to explore. He wants adventure. On top of that, he suspects that something is off about Seahaven. When Truman asks relatively simple questions about the world around him, the people in his life respond with deflection, obfuscation, and gaslighting.

The audience knows something that Truman is on the cusp of discovering: his entire life is an illusion, a reality show filmed in a studio so large it can be seen from space. The show’s producer Christof (Ed Harris) hopes to keep filming Truman forever, even if that means manipulating every aspect of the man’s life, from his friendships to the untimely death of his father.

Still, Truman persists, going so far as to sail a ship to the literal edge of his world. When he finally has an opportunity to escape, to learn the truth, Christof at last reveals himself as a godlike voice in the sky. And by then, the only way he can keep Truman is by playing on his fears. “There’s no more truth out there than there is in the world I created for you,” Christof says. “You’re afraid. That’s why you can’t leave.” But Truman’s not buying it anymore. Threats will not destroy his curiosity. Much like Lily in First Contact, he chooses to take his first steps into a new frontier.

The allegory to apostasy and blasphemy in this scene would be enough to make it a humanist film. But equally important is the theme of commonality with other people. The entire world empathizes with Truman, yet he doesn’t even know that they exist. Only by choosing to step forward into the light, out of the safety of Christof’s illusion, will he find an opportunity to truly connect with other people.

Sorry to Bother You—The soul is the body, and the body is the soul

I was hesitant to include Boots Riley’s bonkers masterpiece here because its science fiction premise comes as a jaw-dropping surprise halfway through the film. But the fact that it’s a mind-bending satire with a big heart makes it perfect for this list.

When hardworking Cassius “Cash” Green (Lakeith Stanfield) gets a depressing telemarketing job, he discovers that the only way to move up in the company is to use a literal “white voice”, which comes out of his mouth like a ventriloquist act (and sounds suspiciously like David Cross). As Cash gets promoted to “powercaller,” he learns that the company is selling something more than just real estate. Meanwhile, his girlfriend Detroit (Tessa Thompson) and his coworkers pressure him to stand up to the corporation, triggering a series of increasingly wacky events that culminate in one of the most surreal uprisings ever filmed.

As an activist and onetime telemarketer himself, Riley brings his personal experiences to bear on the story, and thus the film’s most poignant scenes involve Cash pondering his loyalty to his fellow exploited workers. Anyone who has read Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me—perhaps the most important work of secular humanism in the last decade—will notice some obvious parallels between Riley’s film and Coates’s rejection of divine justice. “The spirit and soul are the body and brain, which are destructible,” Coates writes. “That is precisely why they are so precious.” In other words: don’t bank on some higher power to sort things out. Fix what you can, while you can. Focus on what you know is real. And understand that all of us are trapped in bodies that can be manipulated, injured, or permanently destroyed. This sobering fact connects us, perhaps more than anything else.

Pleasantville—Passion as an act of defiance

The high concept of Pleasantville takes teenage siblings from the 1990s (Reese Witherspoon and Tobey Maguire) and zaps them into a 1950s-style sitcom. This black-and-white universe is so oppressive and bland that it makes Seahaven look like Las Vegas. After taking on the identities of Mary Sue and Bud, these two fishes out of water start making trouble by asking pesky questions like, “What’s outside of Pleasantville?”

This movie could have settled for merely mocking our perception of the 1950s, but there is something more subversive at work here, and the film’s exploration of sexuality and race came as a surprise to most critics. In this world, Mary Sue’s own mother has to ask her what exactly sex is. Indeed, Pleasantville is a place where a sexual awakening—especially for someone who is not a man—threatens the supposedly natural order of things. And when people break this taboo, they appear in brilliant technicolor, making them stick out among the conformists who want to keep everyone in line.

The story takes aim at the insecurity of the conservative “family values” crowd—in particular their lazy notion that the past is perpetually better than the present, which ignores the immense progress that humans have made. At the same time, an observant viewer might ask, what will people decades from now laugh at when looking at our generation? Which arbitrary rules, designed to benefit the privileged few, will shock and astonish historians of the future? By forcing the characters to experience life in Pleasantville, the film challenges both the orthodoxy and complacency that so often hold us back.

High Life—Stoic tenderness when all hope is lost

Directed by Claire Denis, High Life might be the most challenging film on this list, not only because of its bleak premise, but because its ultimate message is open to a wide interpretation. Imagine the most miserable penal colony in the galaxy, populated with the most damaged prisoners and guards, set inside of a spacecraft that is hurtling toward a black hole. Oh, and they’re conducting fertility experiments that will ultimately amount to nothing. Still interested?

Like many of the films above, this one depicts the usual stoicism one would expect from this situation. But its opening scene, in particular, promises something more. In it, lonely prisoner Monte (Robert Pattinson) tries to comfort a baby girl named Willow while going about the mundane tasks of maintaining the ship. Even while on a spacewalk, communicating over radio, Monte soothes the child with a heartbreaking tenderness. A more cutting heartbreak follows as we discover the troubled path that has brought Monte here, and the terrible fate that has befallen the crew. Yet despite this tragedy, the protagonist has managed to become a more loving person, experiencing the fullness of life even within these sterile surroundings.

As the story progresses, we see how the characters have muddled through their isolation—some giving in to hedonistic desires, others adopting a Zen-like attitude. Through it all, the movie does not invite the viewer to judge, only to have mercy. And at the end, when the survivors decide to venture into the unknown, their decision feels well-earned, a natural progression from the more animal-like state to which they descended.

Contact—Discovery as a transcendent experience

Based on the novel by Carl Sagan, and featuring an independent atheist woman as a protagonist, Contact may be the most overtly humanist film on the list. The movie aims for a realistic depiction of humanity’s first attempt at communicating with alien life, as opposed to the more whimsical portrayal in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster) leads the mission, despite efforts from those (men) around her to take credit for her work. But her lack of faith becomes the reason why she is not chosen to become the first person to make contact with the aliens. The scientists instead pick someone whom they feel better represents humanity (again, a man).

In its middle act, Contact is at its sharpest when Ellie and theologian Palmer Joss (Matthew McConaughey) debate meaning and existence. Though brilliant and empathetic, Palmer represents a smarmy, wishy-washy religiosity that attempts to be so inclusive that it arguably becomes meaningless. Ironically, an act of terrorism by a religious zealot leads to Ellie getting a second chance to complete the mission. However, her communication with the aliens is lost in the process, and Ellie has no choice but to ask people to take it on faith that she succeeded. It is a humbling moment for a hero who has relied on reason for the entire story.

In many ways, Contact is commenting on our inability to articulate the transcendent. In a scene that some people love, and others hate, the aliens speak to Ellie in the form of her deceased father—perhaps the most profound way they could connect with her. Afterward, Ellie can describe this experience only in religious terms, leaving people to interpret it according to their own biases. Perhaps this is Sagan’s olive branch to religious believers, acknowledging that we are all trapped on this rock, trapped by our common history—a profoundly humanist conclusion if there ever was one.

But this is not a cause for despair. Similar to the ending of another humanist masterpiece, Cast Away (also directed by Robert Zemeckis), the film closes with a scene of our hero pondering the unknown, and the journeys that lie ahead.

The Future of Humanist (and Post-Human) Science Fiction

There are two trends that could have a profound impact on how these kinds of cinematic stories are told, going forward. First, there is the changing religious and spiritual landscape, which has become even more diverse as people find new ways to construct meaning in their lives, and new means to share them. All the available data that we have on religiosity shows that an unprecedented number of people are moving toward more secular worldviews, at least where polls can be taken. These new categories include not only humanists, but atheists, agnostics, nones, dones, “spiritual-but-not-religious,” and “cultural” versions of traditional religions. A second trend has been the addition of new voices to the film industry—a long overdue development, albeit one that is still moving too slowly.

I wonder if these two movements will lead to a golden age of the kinds of films listed above. Such movies would arrive just in time to examine the impending transformation of the human experience… I’m thinking in particular of climate change, genetic enhancement, life extension, population displacement, space habitation, artificial intelligence, and worker automation, among many others. This possibly posthuman future will require new empathy machines to help us share our dreams and fears, and to better identify with the people who are on this journey with us.

Originally published in June 2020.

Robert Repino (@Repino1) grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps in Grenada, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing at Emerson College. He works as an editor for Oxford University Press, where his projects include the forthcoming Oxford Handbook of Humanism. He has also taught for the Gotham Writers Workshop. Repino is the author of Spark and the League of Ursus (Quirk Books), as well as the War With No Name series (Soho Press), which includes Mort(e), Culdesac, and D’Arc.